Biography: Family and Education

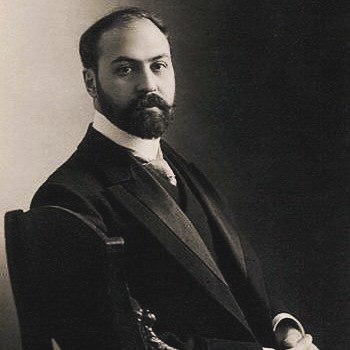

Hasan Pirnia (1250–1314 SH / 1871–1935 CE), born in Na’in, was the son of Mirza Nasrollah Khan Moshir al-Dowleh, the first prime minister (ra’is al-wozara) of the Constitutional era. Hasan completed his early schooling in Iran, then went to Moscow for military and legal studies: he graduated with top honours from the Military School and continued at the Faculty of Law, Moscow University. Returning to Iran, he entered the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a senior secretary and translator. He was fluent in French, English, Arabic and Russian, acquainted with Classical Greek, and—at 58—taught himself German to consult texts first-hand. [1]

Role in the Constitutional Movement and Political Beginnings

On the eve of the Constitutional Revolution, Pirnia took an active role in translating and drafting the electoral by-law and the constitution; together with his brother Hossein (Mo’tamen-al-Molk), he is remembered as a “technical architect” of core constitutional bills. He served as royal translator during Mozaffar al-Din Shah’s second European tour and was later appointed Iran’s envoy to St Petersburg. As diplomat and later minister, he articulated strong legal-political objections to the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention that divided Iran into spheres of influence. [2][3]

Government Posts and Public Offices

Pirnia’s executive record is extensive: three terms as Minister of Foreign Affairs, seven as Minister of Justice (Adliyeh), two as Minister of Education and Endowments, three as Minister of War, and stints as Minister of Commerce and of Post & Telegraph. He represented Tehran in the 2nd through 6th Majles, and he headed government four times as prime minister (1915–1916; 1919; 1922–1923; and 1923). These premierships coincided with major crises: the First World War, Sheikh Mohammad Khiabani’s uprising, the Jangal (Forest) Movement, and the rise of Reza Khan (Sardar-e Sepah). In domestic affairs he is classed as a reformer; in foreign policy, an advocate of neutrality and state independence. [2][1]

Judicial Reforms and the Founding of Modern Procedure

Pirnia stands among the primary architects of modern Iranian justice. Drawing—critically—on French and Russian models and working with jurists and clerics in parliament, he advanced the codification of Civil Procedure (Osol-e Mohakemat-e Hoqouqi), Criminal Procedure (Mohakemat-e Jazaii), and the later Penal Code, instituted competitive examinations for judges and barristers, and is credited with laying the groundwork for the Supreme Court (Divan-e Tamiz) and public prosecution, thereby structuring the modern judiciary. [1][2]

The School of Political Science and Educational Work

One of his most enduring cultural initiatives was founding the School of Political Science in Tehran (originally the “Ministry School”), which later evolved into the Higher School of Law and produced a new generation of diplomats and jurists. Pirnia taught Public International Law there and was hands-on in budgeting, faculty recruitment, and curriculum design—an intervention widely seen as pivotal to professionalising constitutional governance and the civil service. [1][3]

Premierships: Active Neutrality and Defence of Independence

As premier in 1915–1916, amid the First World War, he championed Iran’s neutrality and the evacuation of foreign forces; he rolled back extraordinary prerogatives given to the Belgian customs chief and resisted Russian and British interference in domestic appointments. Allied pressure and the Russian advance from Qazvin to Tehran led to his resignation. In 1919 and again in 1922–1923 he faced the Tabriz crisis (Lahouti), the Gilan/Jangal question (amid Soviet–British manoeuvres), debates on the North Oil concession, press-law reform, and the expanding power of Sardar-e Sepah. His short 1923 “caretaker cabinet” (dolat-e mohallel) had little room to operate; he then withdrew from politics. [2][1]

The 1907 and 1919 Agreements: Legal-Political Resistance

Pirnia opposed the 1907 Convention (spheres of influence) and the 1919 Agreement (British control through financial/military advisers). He answered with international-law arguments defending Iran’s sovereignty, tied any implementation to Majles approval, and removed prematurely installed foreign advisers. Contemporary scholarship and commentary have consequently styled him a “champion of Iranian independence.” [3][2]

Historiography and Major Works

After retiring from politics he devoted himself to research. His three-volume Ancient Iran (Iran-e Bastan, with the school text Old Iran/Iran-e Ghadim) drew on the newest scholarship and archaeological reports of his time; he used inscriptions and Greco-Roman sources (reading Classical Greek himself) and applied comparative source criticism. He also authored Stories of Ancient Iran and a treatise on Public International Law. For method and national historical synthesis, Ancient Iran is viewed as a watershed in modern Persian historiography and remains in print. [1][2]

Historic House and Heritage Status

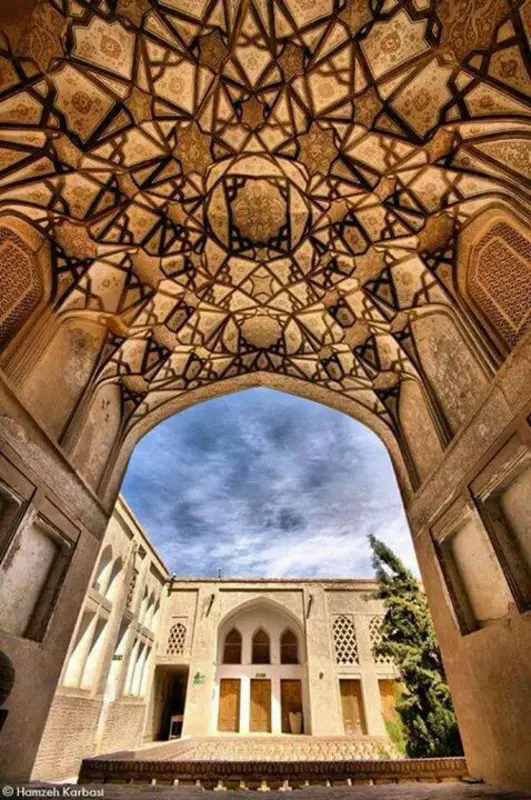

The Pirnia Historic House, situated beside the Jameh Mosque of Na’in (approximately 140 km east of Isfahan), was inscribed on Iran’s National Heritage List in September 1977. It is a benchmark exemplar of residential architecture in Iran’s central desert, preserving the full spatial grammar of traditional houses—entrance and passageways, hashti (vestibule), gholamgardesh corridors, the shahneshin iwan, reception and living rooms, a sunken courtyard (godal-baghcheh) linked to the qanat, and a garden. Its distinguished decorative program comprises refined stucco panels and mural paintings with vegetal and geometric motifs and narrative cycles (including episodes from Haft Paykar), alongside structural and ornamental techniques such as karbandi, Yazdi-bandi, and rasmi-bandi. Formerly the residence of Na’in’s governor—first owned by Qazi Nur al-Hoda and, in the Qajar period, transferred to the Pirnia family—the house was acquired in 1970 by the Ministry of Culture and Art, restored, and inaugurated in March 1995 as the Anthropology Museum of Desert Na’in. Today, through ten themed galleries and more than one thousand objects—ranging from agricultural tools and arms to Qajar-period dress, traditional crafts, and notable pieces such as a four-hundred-year-old Safavid zilu (flatwoven rug) and a three-hundred-year-old double-leaf wooden door—the museum presents a comprehensive portrait of local material culture and lifeways. (Source: Naein Information Portal — http://naeeni.com/home-pirnia-nain/)

Death

Hasan Pirnia died of a heart attack on 20 November 1935 (29 Aban 1314 SH) in Tehran and was buried at Imamzadeh Saleh, Tajrish (family mausoleum). [1]

Final Assessment and Historical Significance

Pirnia is a rare composite of law-centred state-builder and scholar-educator: architect of modern procedure and the Supreme Court/prosecutorial system; founder of the School of Political Science; and a historian who fused documentary criticism with archaeology and classical languages. In foreign affairs he advocated active neutrality and defended sovereignty in the face of the 1907 and 1919 arrangements. This triad—judicial institution-building, educational leadership, and defence of independence—secures his reputation among the most reputable statesmen of the Constitutional era. [1][2][3]

Timeline (Selected Offices & Events)

-

1871 (1250 SH): Born in Na’in. [1]

-

Moscow Studies: Top graduate of Military School; continued at the Faculty of Law. [1]

-

1906/1324 AH: Contributed to drafting electoral by-law and constitution; worked on comparative translations. [2]

-

1907–1908: First term as Foreign Minister; diplomatic protests over the 1907 Convention. [2][3]

-

1909–1912: Repeated terms as Justice Minister; pushed Civil/Criminal Procedure and judiciary reform. [2]

-

1915–1916: Prime minister; neutrality programme, customs reform; resignation under Allied pressure. [2]

-

1919: Short premiership. [2]

-

1922–1923: Prime minister; Tabriz (Lahouti) crisis, Jangal question, press-law reform, North Oil talks. [2]

-

1923: “Caretaker” premiership; withdrawal from politics. [2]

-

1920s–1930s: Authored Ancient Iran, Old Iran, Stories of Ancient Iran, and works on international law. [1][2]

-

20 Nov 1935: Died in Tehran; buried at Imamzadeh Saleh, Tajrish. [1]

Footnotes (Sources)

[1] Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA), “About Hasan Pirnia,” 29 Aban 1399 (Nov 2020).

[2] Persian Wikipedia entry “حسن پیرنیا (Hasan Pirnia),” last updated 23 March 2025.

[3] Ensaf News, Davoud Dashtbani, “Hasan Pirnia, a Champion of Defending Iran’s Independence,” 9 Jan 2024.