The “Central Iranian Sea” is a shorthand for the superposition of several inland lakes and playas at the heart of the Iranian Plateau (the Namak Lake basin, Hoz-e Soltan, Dasht-e Kavir, etc.). During the colder, wetter phases of the Quaternary these water bodies expanded; during the warmer phases of the Holocene they retreated. That gradual desiccation was not merely a physical trend—it triggered a cascade of environmental changes (soil salinization, higher evaporation, instability of surface water) that directly reshaped settlement patterns, agriculture, migration routes, and water-management innovations around the basin—most notably in the Sialk region.

What was the Central Lake?

(A natural “advantage” that gradually turned into a “risk”)

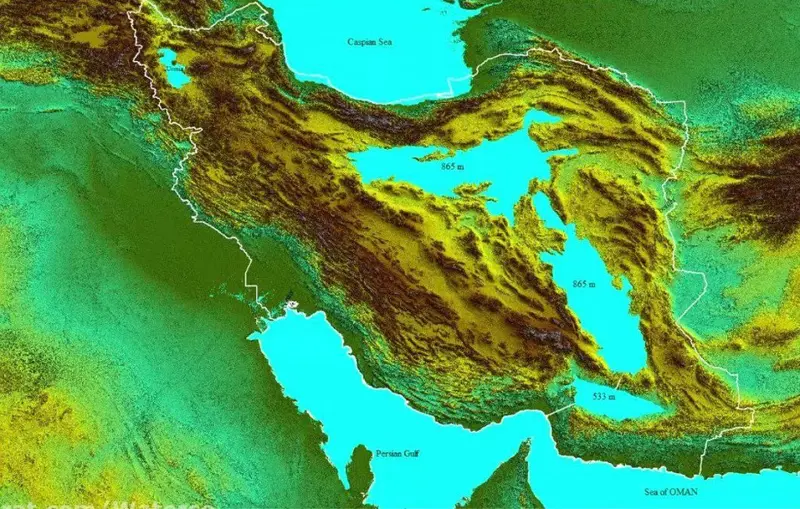

Extensive geomorphic evidence—lake terraces, broad travertine fields, and wide pediments—shows that, at times, interconnected water bodies linked Hoz-e Soltan, Namak Lake, and the “Dry Sea of Saveh.” Three shoreline base levels at 790/800/900 m remain along the margins, marking former lake stages. Along this once water-rich basin, Sialk and a web of early settlements flourished—places where proximity to water made permanent habitation and cultivation possible.

Timeline of Drying: from “cold wet years” to “warm dry years”

Late Pleistocene (Würm glaciation): Reconstructions indicate precipitation about ~48% higher and mean temperatures about ~5.6 °C lower than today, yielding higher lake levels and broader water surfaces in the plateau’s interior. Lake terraces, glacial cirques, and the distribution of travertine corroborate this picture.

Middle to Late Holocene: As warmth increased and effective rainfall decreased, basin water levels dropped. High evaporation, soil salinization, and the advance of evaporites (gypsum/halite/calcite) became dominant. Study of the Sabzevar playa records this transition clearly through a bull’s-eye mineral pattern and brine evolution toward a Na–SO₄–Cl type—capturing the shift from warm–humid to warm–arid conditions.

Mechanisms of Desiccation: why did the water retreat?

1) Long-term climatic backdrop: from “cold wet” to “warm dry”

Paleoclimate reconstructions for the Namak Lake basin show that during the Würm glaciation of the Pleistocene, annual precipitation was about 48% higher and mean temperature about 5.6 °C lower than today. Lake terraces, glacial cirques, and the distribution of travertine corroborate this picture. With the onset of the Holocene, warming and reduced effective precipitation paved the way for declining lake levels and the dominance of evaporative processes. This climatic backdrop is the fundamental driver behind the desiccation of the central lakes.

2) Negative water balance in endorheic basins

A large portion of inland Iran is endorheic—it has no oceanic outlet. Any reduction in inputs (precipitation/runoff) together with increased outputs (evaporation) directly leads to salt accumulation and shoreline retreat. At the scale of the plateau, mean annual rainfall is roughly ~250 mm while potential annual evaporation often exceeds ~4000 mm; even without human intervention, this imbalance yields a negative water budget and advances drying.

3) Sediment–mineral mechanisms and the role of surface evaporation

Sedimentology and geochemistry of the Sabzevar playa show that at the surface, evaporites (gypsum/halite/calcite) predominate, whereas at depth, clastic/alluvial grains (e.g., quartz) increase. Brine evolves toward a Na–SO₄–Cl type, and a bull’s-eye mineral pattern appears (carbonates on the periphery, gypsum in the center, halite to the west)—all signatures of intensified surface evaporation and falling water levels. Seasonal fluctuations in water-table depth plus strong evaporation spread salt crusts and clay-salt pans. Together, these lines of evidence document the transition from a warm–humid past to today’s warm–arid regime and explain the desiccation mechanism.

4) Soil-moisture decline and “breakpoints” in lake levels (recent decades)

Satellite monitoring (1984–2020) shows a significant contraction of lake area across the Iranian Plateau, with breakpoints largely in the late 1990s to early 2000s (around 2001 for the Namak basin). At the same time, annual soil moisture has declined across most basins (up to 39% in some; the steepest drop around ~57% for Gavkhouni), weakening the ability to sustain wetlands and lakes. This marks a structural shift in system inputs and accelerates desiccation.

5) Human pressures: dams, abstractions, and land-use change

Alongside climatic warming and meteorological drought, human activities have played a substantial role in drying lakes/wetlands. For Gavkhouni, specifically, upstream withdrawals and diversions, agricultural expansion and irrigation regimes, and dam construction have contributed to hydrological drought and wetland desiccation. Declines in NDWI/NDVI, in step with reduced inflows, explain the wetland’s repeated dryouts. The same logic applies broadly to other central basins.

6) Climatic feedbacks: dust and local heat amplification

Exposed lakebeds become new dust sources. Analyses indicate that after lakes shrink, AOD/PM2.5 indices rise, with significant negative correlations between lake area and particulates in some basins (e.g., −0.67, with 29–45% of aerosol variability explained by lake-area change). The frequency of dusty events (AOT > 0.5) increases after the breakpoint, and the peak season extends from spring into summer. In addition, Gavkhouni’s desiccation has coincided with higher air temperatures (about +1.6 °C in spring and +1 °C in summer), meaning the “dimmed water mirror” fosters local heat-island effects and further atmospheric instability.

Synthesis of causes

Taken together, reduced inputs (precipitation/surface flows), increased outputs (high evaporation in a warm climate), the endorheic nature of the basins and evaporite accumulation, coupled with soil-moisture decline and, in recent decades, human pressures (abstraction, dams, land-use change), have driven the desiccation of the Central Iranian Sea system. Geomorphic evidence (terraces/travertine), playa sediment–mineral records, and four decades of remote sensing have documented this process step by step.

Direct Impacts on Life and Livelihood around the Namak Basin

Shrinking arable zones. Falling lake levels and rising salinity degraded low-lying soils around the former shorelines; tracts once fertile turned into livelihood risks. Archaeological–environmental readings from Sialk and its hinterland link these shifts to shorter occupation spans on the open plains and a drift toward piedmont zones with more reliable aquifers.

Reconfigured village–route networks. As water retreated and salinity advanced, the center of settlement and exchange moved from the lakeside to foothills and hydrogeologic corridors. Hydrogeologic diversity—not mere distance to surface water—became the decisive locator (a historical inference grounded in climatic and geomorphic patterns).

An evaporites economy. Retreating waters boosted exploitation of salt and gypsum and activated mineral-trade routes—an economic adaptation that strengthened resilience in dry phases.

Sialk in the Mirror of Desiccation: from waterside prosperity to piedmont shifts

Sialk’s trajectory reads like the pulse of the central basin itself. Wet phases with higher lake stands favored agricultural expansion and denser settlement; dry phases encouraged gradual withdrawal from salinizing lowlands, shorter occupation episodes at some sites, and a preference for foothills with steadier groundwater. This “altitudinal movement”—also observed in morphologically similar plains like Qazvin–Tehran—is the most plausible historical response to the drying of the central lakes.

A Technological Response: the Qanat as a “persistence mechanism”

As surface waters grew unreliable, the qanat emerged as an underground solution for stable access to aquifers—making plains habitation viable again, now anchored in collective water governance (turn-taking, shares, mir-ābi water masters). Read against the Quaternary evidence of the Namak basin—terraces, travertines, and repeated wet/dry cycles—the qanat appears as the most logical socio-technical innovation for sustaining life amid desiccation.

A Living Analogy: Gavkhouni as a modern-day lens

The recent desiccation of the Gavkhouni wetland—accompanied by higher air temperatures (≈ +1.6 °C in spring, +1 °C in summer) and reduced vegetation—shows how, when the “water mirror” dims, local heat-island effects and dust risk intensify. This contemporary case offers a tangible model of drying’s consequences and helps interpret past settlement behavior (e.g., gravitation toward foothills and away from saline cores).

Drying, Dust, and Added Pressure on Livelihoods

Time-series analyses for 1984–2020 at national scale show that as lake area declines, AOD/PM2.5 and the frequency of dust events rise (with negative correlations down to −0.67 in some basins and 29–45% of aerosol variability explained by lake-area change). Historically, this means that in dry phases, beyond water loss and soil salinization, air-quality deterioration further eroded the capacity to live and work—an added stressor capable of amplifying migration waves.

Conclusion: Desiccation as a driver of mobility and innovation

The drying of the “Central Iranian Sea” was a continuous, multi-stage process that gradually transformed the locational advantage of lakeside margins into a settlement risk. Communities around the basin (from Sialk onward) responded with a mix of savvy mobility (altitudinal shifts to foothills), crop-system adjustments (tolerance to salinity and low water), and institutional–technical innovation (qanats). This history still guides today’s choices in water governance, wetland restoration, and dust-risk reduction: if we intend to inhabit “drying plains,” we must return to the logic of aquifers and collective water management.

One Response