Rud the Second, like all girls and boys in early childhood, played games, and one of her games was to gather the wool that fell from garments, roll it into a lump, and sometimes spread the thickened wool out flat. The little girl, seeing that her grandfather (Rud’s father) kneaded clay to make pots, also tried to knead her wool, but she could not produce a dough like potter’s clay.

Rud’s father had advanced in pottery and would mix some “angun” (resin) into the clay before making pots. In former times the potter obtained angun from the trees of the neighboring forest, but after the lake and forest dried up, Rud’s father had to go toward the northern mountains to procure angun from the trees on their slopes.

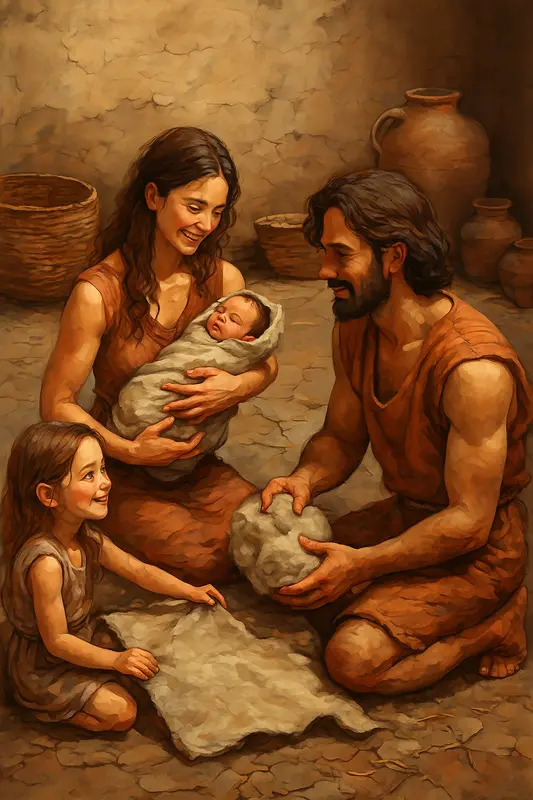

When Rud the Second saw her grandfather mixing angun with the potter’s clay, she set out to mix resin with the small amount of wool she had kneaded. After the angun had been mixed with the wool paste, the little girl spread it out in play; then her childish fancy carried her off elsewhere. When she returned some time later, she saw that her wool had hardened and stiffened; delighted, she showed it to her mother and to the potter-father. Rud took the piece of wool from her child’s hand, wrapped it around her own newborn’s body, and said with a laugh, “It’s clothing.” On that day, without knowing it, Rud the Second invented felt and became the first inventor of clothing!1

Afterward Rud told her followers not to throw away the sheep’s wool that came off the hides, but to knead it and mix it with angun so they would obtain something warm for clothing.

Another of Rud the Second’s amusements was to curl up in the arms of her father, mother, and maternal grandfather, put her fingers into their mouths, and play with their teeth. But the older Rud the Second grew, the fewer teeth her potter-grandfather had.

When Rud the Second reached an age when she no longer played, the potter had no teeth left in his mouth and could not eat cooked wheat unless it was boiled so long it turned into a liquid. To be able to eat wheat, the potter would pound it on a stone to soften it, then gather the pounded mass and put it into his mouth. For years he—and other men and women who had no teeth—pounded wheat on a stone.

One day, haste born of hunger drove Rud’s father to pound the wheat on a stone before cooking it and to eat its flour. The wheat flour gave the potter a new and unprecedented pleasure; he found it sweet and tasty, though he disliked that it turned into a sticky dough in his mouth. Then the toothless man thought to spare himself the trouble of cooking: he would pound the wheat with a stone and, by mixing the flour with some water, make a dough like the one that formed in his mouth, and eat that.

For a time the man ate raw wheat dough, until one day some of the dough he held—just as he was about to put it in his mouth—fell into the kiln fire used for baking pots. After he took the dough out of the fire and tasted it, he realized it was very delicious, and that day the potter succeeded in inventing the cooking of bread.2

Grinding wheat by pounding was a long and tiring task, and the people of Sialk thought to rub the wheat on stone: they would obtain a flat stone, place raw wheat upon it, and then polish it with another stone—moving that second stone from right to left, left to right, diagonally forward and back across the flat stone—until the wheat was ground and could be made into dough. Even today, in parts of Iran—especially in the northern provinces—those who wish to turn some wheat, chickpeas, or almonds with salt into flour at home do it the same way. The earliest Iranian mill consisted of two stones: one large and flat, the other small, to grind the wheat upon the larger stone. The idea of inventing the mill arose from just this: those who rubbed one stone upon another to grind wheat between two stones sought to make the work easier, so that the smaller stone would slide smoothly over the larger without tiring them. After some time, the “hand-mill” (the household grinding stone) came into being, which proved very effective for making wheat flour.

¹ A mythic account of the invention of felt (namad) in Iran.

Archaeological finds from the Pazyryk burial mounds (southern Siberia) include Iranian felt textiles dating to the 5th century BCE, though the origin of felting in Iran is believed to be much older. Felting was among humanity’s earliest textile crafts and has remained a traditional industry in regions such as Kashan and Hamadan.

See: André Godard, L’Art de l’Iran, Paris, 1962 — on the origins and development of weaving and felting in ancient Iran.

² This passage symbolically refers to the accidental discovery of bread baking in early civilizations.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the earliest examples of baked bread in the Iranian Plateau and Mesopotamia date back to around 9000 BCE. Excavations at Tepe Sialk and Chogha Golan have uncovered traces of charred wheat and primitive ovens.

See: Jacques Cauvin, The Birth of the Gods and the Origins of Agriculture, Cambridge University Press, 2000.