Once it was understood that copper could be used to reap wheat, all the inhabitants of Sialk wanted copper and asked the potter to smelt it for them. Tam, who wished to marry Rud the Second, said, “I will not leave Sialk without copper; I must take some to Giyan so that the people there, too, can reap their fields with copper.”

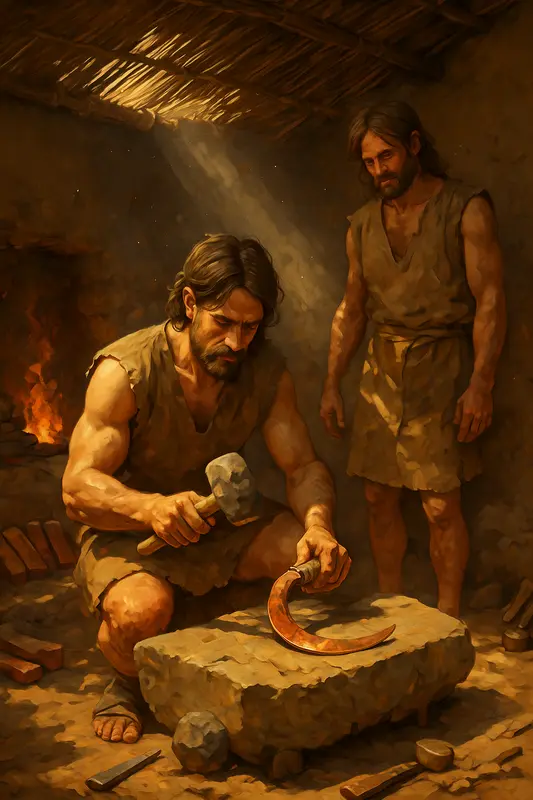

From the next day, the city of Sialk turned into an industrial town, for the potter could not quickly meet the people’s demand for copper. So everyone set out, brought ore-stone of copper, kindled a great fire, smelted the copper, and flattened what they obtained beneath heavy stones, producing sharp-edged tools. Gradually people realized the copper’s edge could be made even sharper, and they discovered that part of a copper sheet could be curled by blows of granite so that it would be easy to hold. Thereafter the sickles of the people of Sialk had handles—handles made of the metal itself.

There was no copper in Giyan or in other Iranian towns, and once people learned of copper’s marvel, they came from all around to Sialk to obtain it and carry it back to their birthplaces. The experience and practice of Sialk’s people solved the sickle problem, and the city’s craftsmen shaped the sickle with blows of granite so that it would not soon tire them when reaping wheat. Rud, the originator of the sickle’s invention, advised her father to make knives and axes of copper, and he, after a short while—and still hammering the copper with granite—shaped the metal as he wished. One day the queen of Iran said to her father, “Copper does not break and can be shaped however we wish; you can make a pot of copper instead of clay.” The potter set about making a cauldron, and the first kettle in that man’s workshop was set upon the fire for cooking food.

When people learned that pots could be made of copper, they eagerly set to work, and in every household large and small copper kettles were made. People from other cities came to Sialk to obtain pots, and the industrial character of that city expanded and grew strong, and Sialk thereafter became the industrial center of Iran.

Sialk’s industrial primacy was established so firmly that thousands of years later that region (including the city of Kashan) remains Iran’s center of copperware, and no other Iranian city has been able to take that distinction from Kashan. Nowhere else in Iran can coppersmiths craft copper vessels with the delicacy of Kashan’s masters; and until thirty or forty years ago, before aluminum ware became common in Iran, any traveler passing through Kashan would take some Kashan copperware as gifts for relatives and friends.¹

This great industrial movement in Sialk did not diminish Tam’s love for Rud the Second; and when Rud, the queen of Iran, realized that her daughter also loved Tam, she consented to their marriage. The wedding was held in the manner previously described in this tale on the occasion of Zab and Rud’s marriage. After the two young people were wed, Rud said to Tam, “Your wife is my successor; after my death she must be queen and Iran-ban.” Tam said, “I will take Rud the Second with me to Giyan, and whenever you bid farewell to life, I will bring her to Sialk so that she may take your place and become Iran-ban.”

When Rud the Second went to Giyan with her husband, she took with her a noteworthy dowry: the method of spinning wool. Today wearing clothing is so ordinary to us that we do not consider how much effort the earliest Iranians—who taught the world to spin thread and weave cloth—expended before they could weave fabric from thread. Had Rud the Second, her husband Tam, and the people of Giyan spun thread but (as will be said) not found the way to weave cloth, the nations of the world would have had to go on wearing skins for thousands of years.

If the Iranian nation had not taught the peoples of the world the ways of life—from cooking food and building towns and smelting metals, to taming and domesticating animals, weaving cloth, and then inventing writing—perhaps even today the peoples of the world would be living in caves and wearing skins, and we would have no literacy to read these lines. For before the Iranian nation became a leader and took on the role of teacher to other peoples, humankind for tens of thousands of years lived like animals; and had the Iranian people not become the teachers of the world’s nations, it is likely that even today humankind would still be living like wild beasts.

¹ Tepe Sialk, located near the city of Kashan, is among the oldest metallurgical centres in Iran. Archaeological excavations have revealed that copper smelting and shaping were practiced there as early as the 5th millennium BCE. The coppersmithing tradition of Kashan continued through the Islamic era into modern times, preserving its reputation for producing finely crafted copperware.

See: Roman Ghirshman, Tépé Sialk: The Prehistoric Civilization in Iran, Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, Paris, 1938.