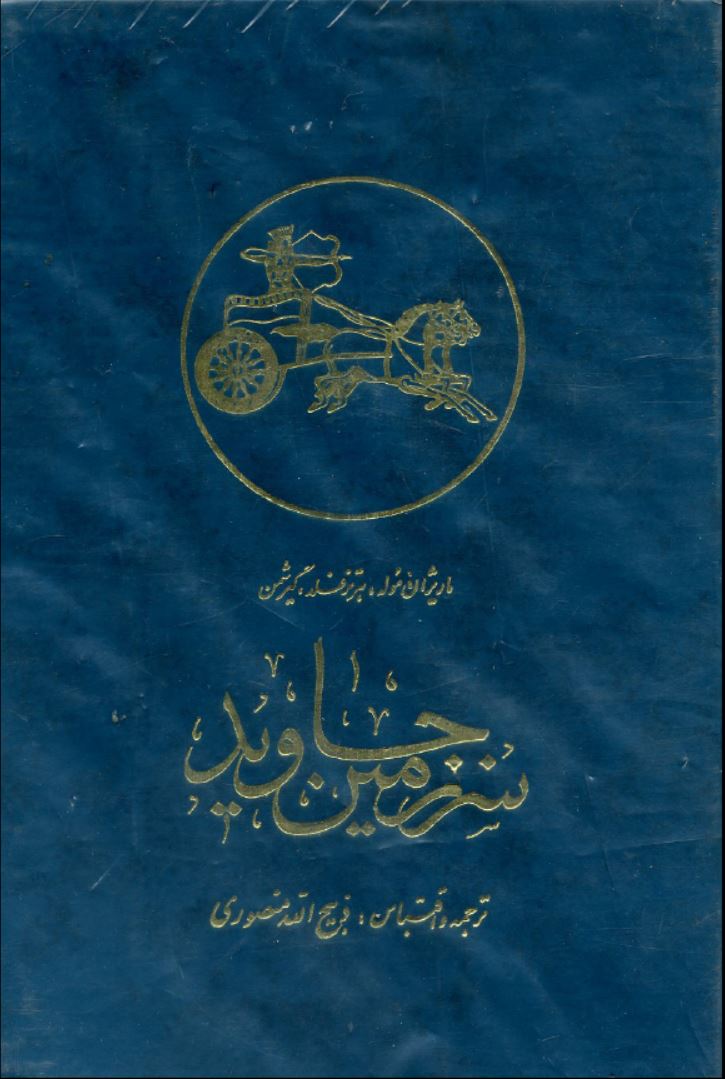

The Eternal Land (Volume I)

From the Works of

Marijan Moulé – Ernst Herzfeld – Roman Ghirshman

Translated by: Zabihollah Mansouri (1889–1986)

Eleventh Edition (First Published by the Original Publisher) – 1999

Print Run: 2,200 copies

Lithography: Ardalan

Printing: Ghiam

Binding: Tajik

Zarrin Publications – Bahar Shomali, Shahid Kargar 35

Postal Code: 15637

Tel: 7509998

Negarestan Ketab Publications – Enghelab Street, Ravanmehr Street, No. 208

Tel: 6406666

All publication rights reserved by the publishers.

ISBN: 964-407-042-9 (Four-Volume Series)

Translator’s Preface

We Iranians are strangers in our own homeland because we do not truly know it.

Our knowledge about our country goes no further than a few classical histories — all of them incomplete and obscure.

In these classical histories, before the introduction, there lies an unknown space, like the surface of Venus, where nothing can be seen — as if before the preface of our history, a bottomless pit had opened and swallowed everything within it.

Even when we reach the written parts of history and seek to understand something, great voids appear.

For example, in place of the long Parthian era — a dynasty that lasted for centuries — there exists a vast gap where nothing can be seen.

Yet those Parthian kings, all Iranians, ruled from the East to the West and could raise armies of three hundred thousand soldiers.

Still, some imagine that they were Tatars!

The history we possess and hand to our youth to read resembles a dead body — lifeless and dull — and therefore no one takes interest in reading it, except for professors who must teach it as part of their profession.

The first person who ever wrote a history of Iran was the late Pirnia, about forty years ago.

That great and patriotic man, however, had access only to French sources and did not know Greek, Latin, German, English, Pahlavi, or Sanskrit — all essential languages for a true history of Iran.

Of course, our intention is not to belittle the work of the late Pirnia or to diminish his legacy.

Pirnia, in writing the history of Iran, is the First Teacher, just as Plato was the First Teacher of philosophy.

Today, every student of philosophy knows more than Plato did, yet so long as the world exists, Plato’s name will remain honoured as the First Teacher.

Likewise, Pirnia will forever be regarded as the First Teacher among Iranian historians.

In the so-called histories of Iran available to the public, there is no trace of the discoveries made in the last forty years — discoveries achieved through the effort and devotion of many dedicated Iranologists.

From Persepolis alone, sixteen thousand inscriptions have been unearthed and deciphered.

These archaeological discoveries have stirred excitement in the world of scholarship, for they reveal that Iran’s contribution to world civilization is so immense that, without exaggeration or vanity, it can be said: whatever the ancient world possessed, it owed to Iran.

This truth must be told to the youth of our nation so that they do not imagine we were mere followers of Western civilization.

We have therefore resolved, within our ability, to introduce our homeland to our compatriots.

The sources of our writing are the historical discoveries of the past forty years and the works written in other languages concerning Iran.

We do not know ancient Greek, Latin, German, Pahlavi, or Sanskrit, but in addition to our own native tongue, we are familiar with English and French.

Thus, we can read the works of international scholars — especially the French and English translations of German researchers — and the studies of historians who, in the last forty years, have unearthed the history of Iran from the depths of the earth.

Were it not for fear of prolixity or being accused of pedantry, we would list all the sources we have used.

However, we suffice with mentioning the three principal names already cited — Moulé, Herzfeld, and Ghirshman — whose works have been our main references.

We humbly admit that whatever we write is derived from others — from learned foreign scholars and historians.

Among the materials we have consulted, part consists of undeniable historical facts, while another part — relating to the earliest ages — is composed of hypotheses and legends formed through the interpretations of researchers.

Naturally, a scholar’s hypothesis cannot take the place of historical truth, yet familiarity with such conjectures is not without value.

Now, as we close this preface, we present to our readers the historical narrative of our land — a story that begins with a captivating legend and gradually enters the realm of historical reality.