Rud suffered greatly in labor. By today’s reckoning, a little more than an hour passed from her first pang until the child was born.

She took the infant in both hands and licked him clean from head to toe; then the child opened his blue eyes. “Your eyes are like your father’s,” she said with delight, and laid him in a cowskin to rest. The next day, when he awoke, she put her breast to his mouth; he drank the milk and fell asleep again.

Women in our age rest for days after childbirth, and until even fifty years ago many died of puerperal fever. But Rud and the women of Sialk did not rest even an hour after giving birth—and they also did not rest beforehand. In their lives, idling before or after childbirth had no place. They did not suffer childbed fever, for there were no midwives to infect them.

During Rud’s pregnancy, Iranban used the dry season to journey south.

They prepared her boat; with tamarisk staff in hand, she boarded, the deer were harnessed, and she departed Sialk along the southern shore.

At that time, Iranians could not cross the lake’s open waters: they had neither sails to tack by the wind nor the means to navigate at night or under clouds. They hugged the shoreline so as never to get lost, and whenever storms roughened the lake they disembarked and waited until the waters calmed.

Without haste, the queen traveled, stopping a day or two wherever her subjects lived. After fifteen days she reached the farthest southern limit of her land—the region of the Dragon. Beyond it lay uninhabited shores.

Iranban had never gone to those empty coasts, but this year a rumor drew her there: people had been seen along the wild shore—short of stature, with black hair and black eyes—who fled whenever the lake people approached, ignoring all calls not to fear.

One day Iranban herself saw them: men and women, short and dark-eyed, staring in wonder at her boat and retinue. As the deer drew near, they ran and vanished. The queen and her companions, taking them to be fearful strangers, called them divs—“the black-haired ones.”

Returning along the coast, she reached a settlement of Iranians. There the locals said: “These divs are strange folk; they eat every creature—even the dragon itself—and perhaps, like lions and elephants, will one day attack us.”

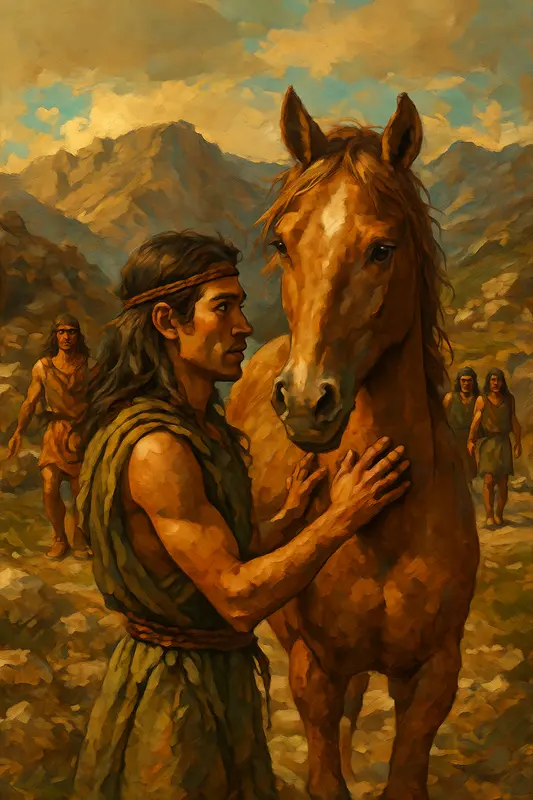

While the queen went south, her son Zab, with two companions, headed into the northern mountains. On his return he brought back two graceful animals never seen along the lake: bright-eyed, with small ears, and long, slender legs—grass-eaters.

No one knew their name; even Zab did not. Iranban named them aspa—“long-leg”—the word we now know as horse. One of them grew so fond of Zab that, after a few hours apart, it would pound a forefoot on the ground when it saw him.

The people of Sialk did not need horseflesh for meat and did not slaughter them; they turned them loose in the meadows and woods about the lake. The horses grew so tame that they would not stray far from town.

One day, as Rud—child in arms—walked with Zab to gather pomegranates, they filled two large baskets they had woven. The friendly horse approached.

“Put the baskets on its back,” Rud said. “Why should we carry them?”

“They’ll slip off,” Zab objected.

“Tie the two baskets together with plant fibers,” she said, “and lay them across its back so one hangs on either side—like a shoulder-yoke.”

Until then, the folk of Sialk carried loads on their backs or with a flexible carrying-pole laid across the shoulders, from whose ends the loads were hung. They chose springy wood so the shoulders would not be crushed; they called that pole jan-chub—“life-wood.”

Zab followed Rud’s advice. He lashed the two baskets together and set them across the horse’s back. The animal did not bolt; it calmly followed Zab.

As they came from the forest, Iranban stood by the lake. Seeing a horse bearing two bulging baskets of pomegranates, she cried out in amazement, and the townspeople marveled as well. Until that day, no one had thought to load a pack upon an animal’s back.

Formerly, their only beast of burden was the deer, which pulled boats along the shallows; a deer could not bear a back-load. There were no carts, and the wind-boats (what Europeans call rafts or sailcraft; the old Persian name is lost) were the sole water-craft.

That day, for the first time in Iran, a tamed animal—the horse—was used to carry a load. Even Iranban, the wisest in Sialk, could not say when dogs had first befriended Iranians and guarded them against lions, elephants, and other perils.

Delighted, the people tried to load other horses, but those were not as gentle as Zab’s. When loaded, they reared, kicked, and fled.

Yet the patience of Zab’s horse taught Sialk that horses could be pack animals. Many men went north to the mountains and brought back horses and mares; they loosed them in the meadows and woods, and soon large herds grazed around the lake.

Another rainy season arrived, slowing life in Sialk once more. People could not travel the forests, yet they lacked nothing for food; wild ducks were so abundant that they took as many as they liked. They did not use the feathers—there was no need yet, with hides so plentiful for clothing, bedding, and cover.

Often the queen lifted her staff toward the sun and told her people: “All we have is from Khur. He has given us deer, fish, and ducks; he has made dogs our companions and guardians; he gives us water to quench thirst and fire to cook fish, duck, and venison, and to harden our pots.”

Three years before Zab’s wedding, his father had fallen from a mountain and disappeared; from then on Iranban lived without a husband. The man had gone after a creature that lived only on the cliffs—never descending for fear of the wolf—a beast the ancients called the “little cow,” for the cattle grazed the lower slopes while these were seen higher up. That “little cow” is what we now call the wild sheep. In some Iranian ranges it still lives, much like the domestic sheep, only fatter and heavier-fleeced.

When Zab’s father fell, a river in the deep ravine below carried away the body. Some who knew the lay of the land said that river did not flow into the lake but north toward the sea; thus his corpse was lost.

His death changed nothing in Sialk’s governance: as the queen’s husband he had no authority, and for all affairs people turned to Iranban, whom all deemed wiser than men.

After three years, once Zab married, he decided to find a husband for his mother. Many widowers desired Iranban—not for power, for marriage to her brought none, but for her beauty. Zab would not favor one over another, for all were tall, strong, and broad-shouldered.

He gathered them by the lakeside in the forest, chose several straight, equal-height plane trees, and announced a contest: whoever climbed to the top first would be the queen’s husband. The winner married Iranban, and the wedding feast mirrored Zab and Rud’s: in Sialk they celebrated widows’ marriages no less than those of youths.

Summer ended, autumn began—the prelude to the rains.

One night Rud woke to the crashing of tens of thousands of branches. She roused Zab.

“Listen.”

“Deer! Deer!” he cried.

Men and women poured from their houses with stone-tipped axes and spears, running toward the sound. A vast migration of deer was passing; their antlers struck together with a noise like trees colliding in a storm.

The townsfolk fell upon them—not chiefly for meat, which they had in plenty, but from hostility: each year, when the wild herds migrated north, they would lure away some of Sialk’s tame deer; even some domesticated deer turned wild and followed them. The people blamed the wild herds for their losses.

All through that night and until near sunset the next day the deer passed, and the people killed as many as they could—to use their hides and bones for clothing, bedding, and gear.

Never before had so many deer traveled in one immense mass; usually they went by separate herds, making slaughter difficult. This time, after the migration ended, the townsfolk sought to skin the carcasses—but there were too many. Soon the bodies rotted, and a stench filled Sialk.

Even Iranban did not know at first how to rid the town of the foul air.

Rud’s father said: “We must drag the carcasses away—north, into the ravine.” Zab sailed to summon help; people came by boat and by land, and together they hauled the bodies off and hurled them into a northern gorge. The air grew clean again.

The rains had not yet begun when Iranban fell ill. In Sialk, the familiar illness was what we now call a cold—an autumn ailment that troubled people two or three days and then passed. But this time, when Zab came to her, he found her unable to eat, asking only for water.

Her husband said: “For days she has taken nothing but water; if she refuses food, she will die.”

Zab pleaded: “Mother, why won’t you eat? A person should eat five times from sunrise to sleep, and also partake of all the fruits Khur bestows. You yourself taught us that to spurn the fruits angers the sun. Yet now you refuse.”

“I am ill,” Iranban said, “and can only drink water.”

“Everyone falls ill,” Zab replied. “Two years ago I was sick, yet I did not stop eating: a duck at dawn, fish at midday, venison or duck in the afternoon, and two more meals toward night.”

But Iranban could not eat. Two days passed, then three, and her sickness did not abate. That was when the people of Sialk and the queen herself understood: this was not the ordinary autumn ailment—it was something else.

That same day, several others fell ill with a sickness like Iranban’s.