The woman’s concern pleased Iranban, for it showed care for the herds. Then someone in the crowd said:

“In the north, some people don’t eat duck or fish or venison or beef. They eat wheat and barley.”

“I told them,” said Iranban, “that eating wheat makes a person ugly and weak.”

A man called out: “We never eat wheat. Wheat is food for our deer and cattle; it fattens them.”

“Yes,” Iranban replied, “wheat makes humans ugly—and, besides, it brings misfortune.”

A woman asked: “How does it bring misfortune?”

Iranban answered: “I heard it from my mother, who heard it from hers: if a human begins to eat wheat, the day will come when his food will be nothing but wheat, and he will find no other nourishment. Let the wheat rot on the mountain slopes; do not gather it—especially do not eat it—so that Khur will not be angered with you.”

As she spoke the name of Khur, she lifted her tamarisk staff toward the sun. A hush of reverence fell over those present; all eyes turned upward in respect.

Iranban’s companions unbound the deer from the boat and released them. The animals took the path along the reeds and vanished.

The queen’s audience, having spoken enough, also went their ways to take their meals. Outwardly the people looked alike, and so did their food: most ate fish and wild duck; after those, beef and venison were their staple meats.

As yet, there was no agriculture in Iran, nor did anyone feel the need of it. Meat was so abundant that there was no hunger to force tilling the earth. The wise only feared that the day Iranians began to eat wheat, misfortune would begin—because farming would follow, and with it dependence on land.

Wheat grew wild on the mountain slopes; it sprouted and withered away. No one gathered it—save a few capricious folk who sought novelty and taste.

Iranban’s house in Sialk was no different from other houses.

Sialk consisted of clusters of homes built upon or along the hills overlooking the lake, each dwelling set apart from the next by what today would be two hundred to five hundred meters. All were wooden structures roofed with thick thatch cut from the lakeside reeds. Once a year, when the reeds were tall and ready, they renewed the roofs.

In the rainy season—which began in autumn and lasted without break until halfway through spring—not a drop leaked into the homes; yet the rains were so heavy and long that when they ended, the lake had risen by ten to fifteen meters. For this reason, houses around the lake were often set on piles to keep them safe when the waters rose.

In Sialk, everyone knew that when the rainy season ended, Zab and Rud would marry; the town looked forward to the celebration.

The long rains wearied all, even the deer; only the wild ducks and geese seemed delighted beneath the clouds. During that stretch of downpour, life in Sialk nearly halted. Men did not go out to row the boats; from every house came the sound of stone being chipped, for they spent those days shaping axes, knives, and arrowheads.

Before the wedding, during the rains, Rud sat at home sewing her garments with a needle made from deer bone, and making shoes for herself, her father, and her future husband. She chose the soft hide of fawns for clothing and the thick hide of old stags for footwear—a leather they called kal-charm, “thick leather.”

Near Sialk, a patch of red earth appeared each year when the ground, loosened by rain, slid and washed away. When the rains ceased, the reddish silt settled in the low hollows. The people of Sialk called that settled earth kuz—red clay.

Rud’s father, a potter, would go out after the rains, gather the clay, shape vessels by hand, and fire them until they were as hard as stone. The townsfolk traded him hides and horns of deer and cattle in exchange. Hence they called him the potter.

When the rains finally ended, the sky turned the color of the lake, the sun poured over the world, and hundreds of thousands of birds sang on the branches along the shore. From every house in Sialk rose the shout “gil… gil… gil…”—the town’s cry of joy.

Rud and Zab cried gil louder than the rest, for they knew their wedding day had come.

As Rud lifted the pots her father had made to ready them for sale, one vessel slipped from her hands—yet it did not break. Instead, it rang with a strange, unfamiliar tone.

Startled, she picked it up and examined it; it was unlike the others her father took from the fire. She let it fall again; once more it would not shatter. Bewildered, she ran, shouting, to find her father.

He tested the vessel and agreed: this pot did not break when it fell.

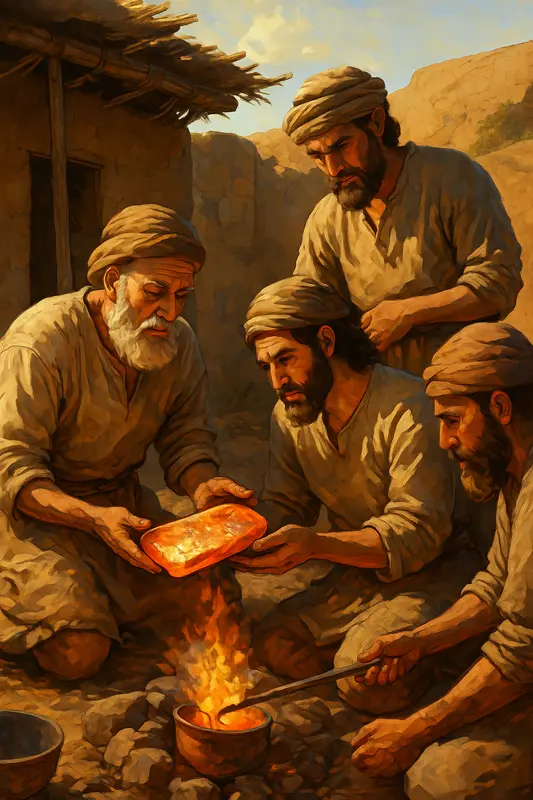

Though neither he nor his neighbors had the learning of later ages, Rud’s father grasped that the clay used for this pot differed from the usual red earth.

That day, without knowing it, he had opened a new gate for the Iranians—for mixed into that red silt was the wash of a copper vein. The first hint of copper came to light in the land of Sialk (near today’s Kashan), and for the first time on earth, people there discovered the metal.

If dowries had been customary in Sialk, this new kind of vessel would have been the finest gift a father could give his daughter. But dowries belonged to later ages, when marriage became trade and transaction.

At last, the day all had awaited arrived: the wedding of Rud and Zab. By the queen’s order, the ceremony would be held in the center of town, by the lake.

Women adorned stag antlers with fresh greens; men brought heaps of fish and wild ducks, and even slaughtered a deer for the great feast.

No one offered formal congratulations—rituals had not yet been invented. Formalities, they say, are born when love disappears and must be replaced. The people of Sialk were simple and loved one another; the joy of one young couple was the joy of all.

When they had eaten their fill and slaked their thirst with clear water, they struck drumskins stretched over clay jars, and at the sound of drums everyone began to dance. Iranban, too, danced among them.

Their hair—men’s long locks mingling with their beards, and women’s tresses flowing—made a scene that would seem wild to the people of our time. They danced until they fell asleep from weariness upon the lakeshore, and the drums fell silent.

Toward night, the cries of wild ducks alighting in the reeds woke them. Men ran to the town hearth, brought fire, and built a great blaze beside the lake. In Sialk, no festival was complete without fire; its flames kept watch until morning.

After the wedding, Rud left her father’s house to live in the home Zab had built. Soon she conceived. With no mother to instruct her, it was Iranban—her mother-in-law—who taught her the ways of childbirth.