The initial script of the Iranians was (most probably) something like pictographic writing, and after some time they were able to invent an alphabet, and that alphabet was so noteworthy that seven thousand years ago it sufficed to meet the needs of writing; and after we enter the historical stages of Iran (that is, the period for which written history is available), we see that the Iranians brought the alphabet to such a degree of perfection that none of the alphabets of today’s world can rival it, and this is a sign of cultural development in ancient Iran.

In the historical period, the Iranians had three types of alphabet: one for writing books and religious texts, another for writing books and ordinary matters, and a third for writing everything; and all sounds, even the sounds of birds and mammals and the sound of wind and sea waves and the falling of waterfalls, and, even more so, musical melodies.

The third alphabet of the Iranians was not only an alphabet but also musical notation, and with it they could write every kind of sound and play every kind of melody.

Those melodies do not exist in Iran today, but they exist in Armenia, and a part of the authentic Armenian melodies consists of melodies that they adopted from the Iranians with the same ancient notation; and anyone who doubts this matter may consult an Armenian musician of the rank of masters (not beginners) in order to know that this statement is correct.

The alphabet that the Iranians invented, in addition to meeting their needs and placing the key to knowledge and culture at the disposal of humankind, was also beautiful in form.

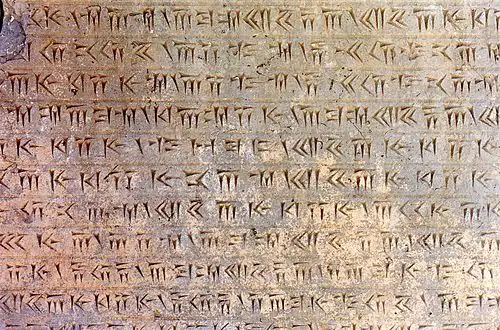

It suffices to look at one of the cuneiform inscriptions that has remained from the Achaemenid period to realise that the alphabet of the Iranians is one of the most beautiful alphabets in the world, and in terms of order, arrangement, and proportion it has no equal even today, and neither the Latin alphabet nor the alphabets of Eastern peoples possess the order, arrangement, proportion, and, in a comprehensive sense, the beauty of cuneiform script.

The inscriptions that remain today from the Achaemenid period are written in an alphabet that the Iranians used for ordinary matters; nevertheless, that same ordinary alphabet was so complete that with it they could write the languages of the peoples of that period, as evidenced by the fact that some of the Achaemenid inscriptions were written in different languages but with a single alphabet.

Among historians there exists a debate indicating whether Iranian writing and alphabet were first invented in Armenia or in Iran, and this debate has arisen because historians view the political divisions of the world through modern eyes, whereas in the period that we conventionally call the pre-historical era, Armenia and Iran were one country and one race lived in both, and even today their appearance and physique show that they are of one race.

However, the inscription that proves the antiquity of Iranian writing and alphabet in relation to other scripts and alphabets was discovered in Iran, not in Armenia.

The antiquity of Iranian writing and alphabet should, by rule, be more than seven thousand years, because seven thousand years ago the Iranian alphabet already possessed maturity; and since an alphabet does not reach perfection all at once and it takes time for its defects to be removed and its shortcomings remedied, we can say that the alphabet in Iran may have been invented eight or nine thousand years ago.

Regarding the invention of writing in Iran, one cannot consider a single individual, because it is not unlikely that writing—that is, a sign that conveys a word or a sentence—was invented simultaneously by a large number of people.

Even today, in all places where people are illiterate, they convey some words or sentences to others by means of certain signs, and such signs are called “ideograms” in Latin.

Since the Iranians most probably invented writing and the alphabet for writing religious laws and invocations, it can be said that the first religious book written in the world was composed in Iran, and this undermines the antiquity attributed to the Book of the Dead, which was written in Egypt.

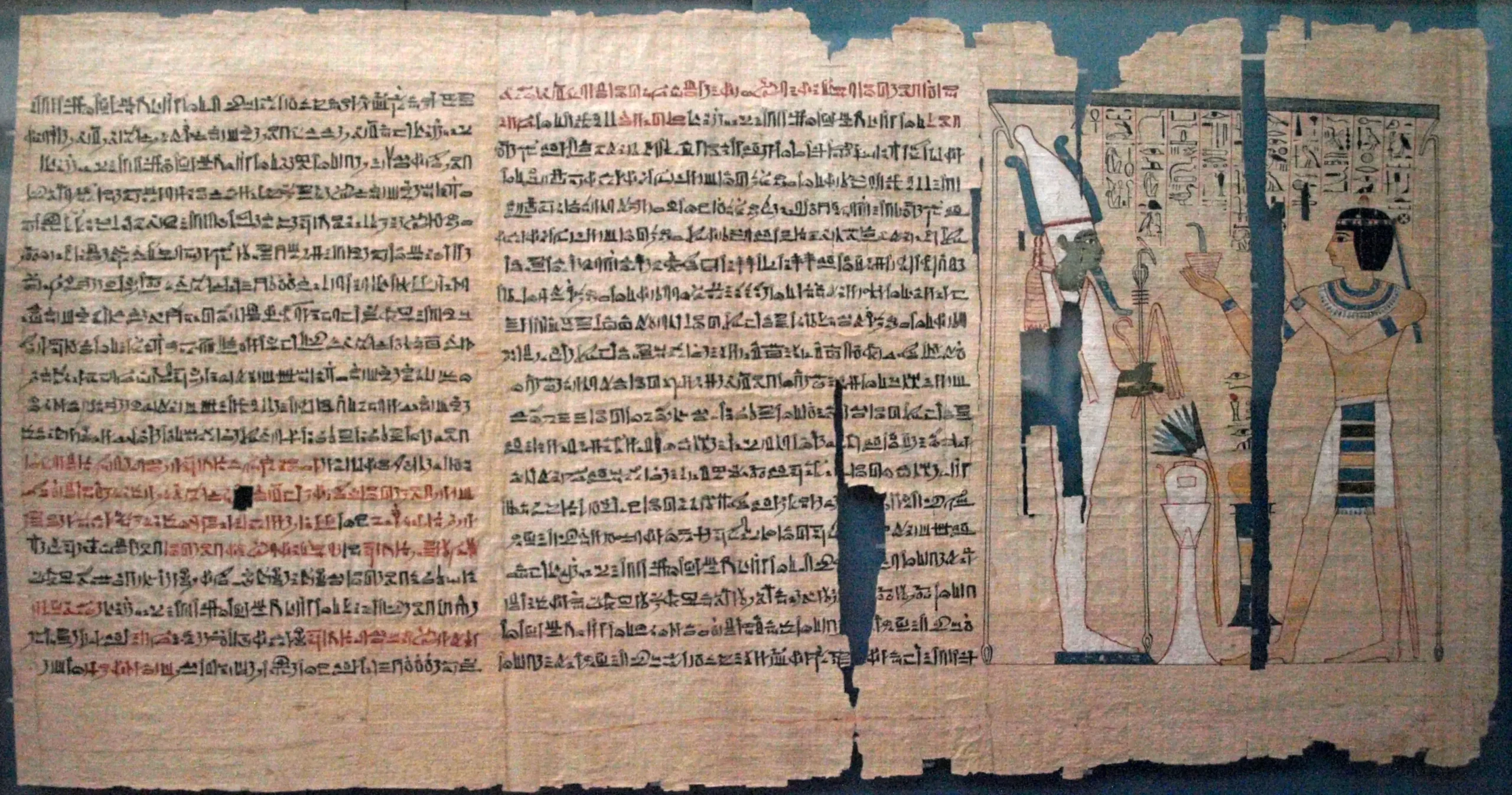

Until today, the belief of historians regarding the oldest written book in the world was that the oldest among them was the Book of the Dead of the ancient Egyptians.

Perhaps before any book was written, religious beliefs were transmitted orally for thousands of years, until the Book of the Dead was written in Egypt, and Egyptologists have considered its antiquity to be six thousand years, and some of them have said five thousand years. That book contained the religious laws of the Egyptians and does not exist today, but parts of it can be seen in some Egyptian inscriptions.

The script with which the Book of the Dead was written was the ancient pictorial script of Egypt, and at the time the Book of the Dead was written and for some time thereafter the Egyptians did not have an alphabet; but since seven thousand years ago the Iranians possessed writing and an alphabet, can it not be assumed that those who invented writing to record religious laws and invocations also wrote the world’s first religious book?

Perhaps in the future documents will emerge from the soil of Iran that confirm this assumption.

In Iran there are many mounds that are signs of ancient cities and have not yet been excavated to obtain historical remains, and it is probable that after excavations in those mounds other documents will be found that push the antiquity of Iranian writing and alphabet further back.

Some historians, based on conjecture, have supposed that in ancient Iran reading and writing were exclusive to religious leaders and in later periods exclusive to religious leaders and scribes, whereas in ancient Iran everyone—that is, both men and women—read and wrote, and reading and writing were not confined to a specific class; the reason everyone read and wrote was that reading and writing were among religious duties, and everyone had to acquire literacy in order to be able to read religious texts.

“Herodotus”, who was both a historian and a writer and had seen some of the things he wrote about in his histories with his own eyes, wrote in the book The Wars of Iran that Iranian soldiers were literate.

At that time most Greek officers were illiterate, and even “Leonidas,” the king of Sparta, whose battle with three hundred soldiers in the strait known as Thermopylae against Xerxes, the king of Iran, is famous, knew only the rudiments of reading and writing and was not able to read and write fluently, and among his three hundred brave soldiers who were killed at Thermopylae there was not a single literate person.

Although in Iran during the Achaemenid period people were divided into several occupational classes (the foundations of which had been laid some time earlier), there were neither class hierarchies in the sense of material superiority nor discrimination in education and upbringing; and the Iranians believed that just as they had to work to sustain life, they also had to learn reading and writing in order to read religious texts.

One of the reasons for the literacy of Iranians even at the end of the Achaemenid dynasty—that is, in a period when Iran did not enjoy the educational prosperity of the beginning and middle of the Achaemenid era—is that in all Iranian households books, especially religious books, existed, and if the Iranians had not been literate, books would not have been found in their homes.

Considering reading and writing obligatory and counting them among religious duties had become so ingrained in the nature of the Iranians that it did not disappear even after the Arab conquest of Iran, and a number of Iranian scholars in the most degenerate scientific periods of that country—that is, after the Mongol invasion—believed that the pursuit of knowledge was among religious obligations, and just as they regarded prayer and fasting as obligatory, they also deemed the pursuit of knowledge necessary.

Endnotes

If systematic excavations are carried out in Iran, it is not unlikely that evidence and documents will be discovered proving that the Iranians were the world’s first teachers of writing and the alphabet — Professor George Cameron, renowned Iranologist.